The Gloria Patri and Inclusive Language

by Richard L. Floyd

The basic question before us is whether it is any longer acceptable to use the name of “the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit” in Christian discourse, and, more specifically, in Christian worship. That this is more than an academic concern is apparent by the fact that my denomination, the United Church of Christ, in its Book of Worship, 1986, decided that it would not use that formulation in its liturgies, except in the baptismal formula (for ecumenical reasons), and, inexplicably, in the “Brief Order for the Service of Word and Sacrament” (p. 79).

As the first denomination to accept such a thorough-going agenda to eliminate masculine language about God, the UCC will be judged by history either to have been a bold pioneer blazing the trail for others to follow, or to have been merely the most zealous in acting out the persistent death-wish of mainline Protestantism by cutting its moorings to scripture, tradition, theology and ecumenism.

The issue is often cast in the terms of a feminist critique versus traditional articulations of Christianity, but the playing field is a far larger one than that. This discussion is a symptom of a major epistemological struggle taking place in the Post-Enlightenment world of which we are by necessity a part. The real issue here is whether God named as “Father, Son and Holy Spirit” or by any other trinitarian euphemisms has any place in the “plausibility structure” (to use Peter Berger's category) of the humanistic, scientific, and secular “world” which dominates cosmopolitan life in the West, including (I would say particularly) in the academy.

I contend that God so named has been deemed to have no place, and, therefore, attempts are taking place to find a God more in line with the plausibility structure. In the academic world from which our seminaries and bureaucratic elites derive their ethos, those attempts have been going on with vigor for decades. That this “plausibility structure” is itself a faith, an alternative faith I would contend, is seldom understood, but no less dangerous for being so.

I have been asked to examine the issue of trinitarian language in our liturgies with special attention given to the second person. I would like to focus particularly on the use of “the Son” in the Gloria Patri and compare its theological meaning with that of one of the major revisionist alternatives, “the Christ” as used now in the Gloria of the United Church of Christ Book of Worship. Clearly such an analysis cannot be undertaken apart from some reference to “the Father” and to a lesser extent also to “the Holy Spirit.”

The most often employed way to duck naming the first person of the Trinity “Father” is by substituting the word “Creator.” This substitution satisfies not only the feminist critics, but also others whose plausibility structure finds a nature-God more congenial than the God of the Bible. There are any number of problems that arise from this substitution, not the least of which is that “Creator” can aptly be used to describe the work of not only the first person but of all three persons since creation is a work of the Godhead, and not of any one person of the Trinity, as a quick look at Genesis 1 and John 1 will show.

This substitution of “the Creator” for “the Father” is used in what Geoffrey Wainwright has suggested is probably the most favored among the alternatives currently being used in North America: “Creator, Redeemer, and Sustainer.” This particular formulation risks the ancient heresy of Sabellius who saw in the three persons three aspects or phases of the activity of the Godhead toward the world. (“The Doctrine of the Trinity” Interpretation, April 1991, p. 121)

But for our discussion “Creator” is principally flawed as a substitute for Father because it in no way represents the intimate relationship between the first and second person signified by Father and Son, a relationship critical for understanding the dynamics at work within the Trinity and for any adequate soteriology which might be understood to arise from that relationship. The constellation of meanings around the notion of “inheritance” is also lost when we cease to speak of the relationship of the Father to the Son, meanings also critical for soteriology. The doctrine of the Trinity has profound soteriological implications, which have often been lost in liberal Protestantism's reductionism, even before it started to muddle the language; witness Schleiermacher who was practically unitarian and never developed much of a place for the Atonement in his system except as the apotheosis of human sacrifice.

In discourse about the Trinity, theologians distinguish between the immanent or essential Trinity, what God is in God's own being, and the economic Trinity, what God does in the world. The alte

rnatives to “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit” suggested by the revisionists invariably substitute economic language for immanent language as a way to avoid naming God with the offensive masculine language, but what they do not accomplish is to name the Trinity at all. For example, “Creator, Redeemer, Sustainer” doesn't name the Trinity, but merely describes three economic terms, all of which involve all the persons of the Trinity. They say what God does, but not what God is.

rnatives to “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit” suggested by the revisionists invariably substitute economic language for immanent language as a way to avoid naming God with the offensive masculine language, but what they do not accomplish is to name the Trinity at all. For example, “Creator, Redeemer, Sustainer” doesn't name the Trinity, but merely describes three economic terms, all of which involve all the persons of the Trinity. They say what God does, but not what God is.John Wesley anticipated the inadequacy of such economic formulas as substitutes for the trinitarian name when he wrote in a letter in 1771: “The quaint device of styling them three offices rather than persons gives up the whole doctrine.” (Wainwright, p. 121) He understood that the name “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit” expresses essential internal relations within the Godhead, which are evidenced in the biblical narrative; relations of personal communion and cooperation among the persons of the Trinity that are not expressed by the functionalism of the alternatives.

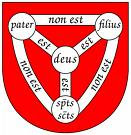

Let us look at the Gloria Patri, the most widely used canticle in the church, as one of the principle liturgical expressions of the Trinity. The Gloria Patri is known as the Lesser Doxology to distinguish it from the Gloria in excelsis, or Greater Doxology. This ancient canticle of the church is an ascription of praise to the Trinity. The first part, “Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit,” is based on the dominical great commission found in Matthew 28:19. It may have come into use as early as the second century in both the Eastern and Western church. Its use at the end of the Psalms to give them a trinitarian character is attested from the fourth century, which is also when its second half was added, “as it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be . . . ” which was intended to counter Arianism by affirming that the Triune God of the New Testament is the same divine being as in the Old Testament, something the Arians denied.

Now let us look at what the UCC has done to the Gloria Patri, or Gloria as it now must be called since there is no father to be referred to even under the cloak of Latin. The Gloria from Book of Worship is:

Glory to God the Creator,

and to the Christ,

and to the Holy Spirit:

as it was in the beginning,

is now,

and will be for ever.

Amen.

In the UCC Gloria we have now begun to speak of the Trinity in code, known only to those who know that “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit” are what we mean when we say “Creator, Christ, and Holy Spirit.” But when those of us who know the old code have gone, will new generations of Christians be able to speak intelligibly about the Trinity? One wonders.

Besides, the code is fraught with theological dangers. Perhaps most significantly, “Creator, Christ and Spirit” are even more susceptible than “Creator, Redeemer, Sustainer” to the Arian tendency to view Christ and the Spirit as mere creatures. This carries with it, to use Wainwright's words: “the unfortunate possibility of divine authentication for a natural order in its fallen state. Without a christological and pneumatological qualification (i.e., without the redemptive work focused in the Son and the transformative work focused in the Holy Spirit, the three persons being in divine communion), the ‘Creator’ now becomes responsible for creation in its disordered condition . . . a danger when the notion is cut off from the full biblical narrative on the basis of which a properly trinitarian God was seen by the church to be a saving necessity—now graciously self-revealed.” (Wainwright, p 122) A “Creator” thus detached from the trinitarian substance, so carefully articulated by tradition to capture the nuances of the biblical narrative, leaves us in the precarious situation of having a Gospel for which we have no need. Most religions claim God as Creator, but the trinitarian faith has some very particular claims to make about God and creation that are in danger of being obscured (and, in fact, are obscured in some of the newer “Creation Theologies” of which the writings of Matthew Fox seem to be the most popular example.) Some of the Eastern religions might well accept a “Creator” deity with an anointed “Christ” as having some special divine status, as an avatar perhaps, but this hardly represents the particular claims of Christian faith about the relations between the first and second persons of the Trinity.

In light of these dangers to the integrity of Christian theology and liturgical expression I consider the present time to be an “Athanasian” moment. What is at stake is nothing more nor less than our doctrine of God. “Creator” and “Christ” will not carry the theological freight. Economic terms are not adequate substitutes for immanent terms, for in Christian theology what we know about creation follows rather than precedes what we know about the nature of God. As Athanasius said, “It is more pious and more accurate to signify God from the Son and call him Father, than to name him from his works and call him Unoriginate.” Thomas Torrance puts it like this:

“To know God in any precise way we must know him in accordance with his nature, as he has revealed himself—that is, in Jesus Christ his incarnate Son in whom he has communicated not just something about himself but his very Self. Jesus Christ does not reveal the Father by being Father but by being Son of the Father, and it is through Christ in the one Spirit whom he mediates that we are given access to God as he really is in himself. In contrast with Judaism and its stress on the unnameability of God, the Christian Faith is concerned with God as he has named himself in Jesus Christ, and incarnated in him his own Word, as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Jesus Christ is the arche, the Origin or Principle, of all our knowledge of God, and of what he has done and continues to do in the universe, so that it is in terms of the relation of Jesus the incarnate Son to the Father, that we have to work out a Christian understanding of the creation. It is the Fatherhood of God, revealed in the Son, that determines how we are to understand God as Almighty Creator, and not the other way round. It was through thinking out the inner relation of the incarnation to the creation that early Christian theology so transformed the foundations of Greek philosophy, science and culture, that it laid the original basis on which the great enterprise of empirico-theoretical science now rests.” (The Trinitarian Faith, p. 7)

Given Torrance's observations about the name of the Trinity it is interesting to me that Phyllis Trible's article on the “Nature of God in the Old Testament” (in the Supplementery Volume to the Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible) is cited in Book of Worship as a principal source for the decision to eliminate masculine language about God. Her point about the need to expand the vocabulary of images with which we talk about God to include female imagery is surely well taken, but there is no precedent in scripture or tradition where God is named using female names, and to do so, as Book of Worship has, is to embark on a radically new enterprise.

To add Mother to the name of the first person of the Trinity, as both the Inclusive Language Lectionary and Book of Worship have done is a curious decision, given the identification of mother language with Canaanite fertility religion in the Old Testament, and the place of Mary, the Mother of God, in the New Testament and subsequent Christian tradition. Elizabeth Achtemeier has repeatedly raised the charge that a “Mother/Father” God makes hash of the role of Mary as portrayed in scripture and tradition. We might do well to recall that the title Theotokos for Mary was primarily a christological affirmation of the unity of Christ's person and only secondarily to promote the veneration of Mary. That its formulation in the fourth and fifth centuries roughly coincided with the trinitarian and christological formulations of Nicaea/Chalcedon that we have been considering in Confessing One Faith is suggestive that these issues should not be separated.

We could probably all agree that it is just and right and highly desirable to expand the metaphorical base of our speech about God, especially the lost traditions now being recovered from the scriptures, but that is not the issue here. What is at issue is which God will we be using our expanded metaphorical base to describe? Is that God named in ways that are consistent with the Word of God as attested in scripture and maintained by the great tradition of the ecumenical church? At those key moments when the church names God, especially at moments of praise and during eucharistic prayers and at baptism the church names the Triune God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit, as our ancestors have for nearly two millennia, not to describe God's attributes, God's works and deeds, but to confess which God it is we are worshiping.

The difference between describing God and naming God is critical for a proper understanding of these issues. There is, to take one example, an important distinction to be made between the descriptive use of the term “father” to show God's compassionate care for humankind (as in Psalm 103:13) and Jesus' use of the name “Father” as an address for God. “Father” in the former sense could as easily have been “mother”, and sometimes is in scripture. Some confusion exists in cases like this when all biblical images are reduced to the great grab bag of the category of metaphor. (See, for example, Sally McFague, Metaphorical Theology, 1982 or, much better, Janet Martin Soskice, Metaphor and Religious Language, 1985) Clearly in the example above, the “father” who pitieth his children functions quite differently from the “Father” of our Lord Jesus Christ. The former is a metaphor, the latter, while metaphorical, is the name which Jesus chose to call God and taught us to do so as well, and, therefore, might correctly be put under the heading of “the scandal of particularity.”

Let me be quite clear about what I am not saying. I am not saying that God is male; Christian discourse about God and liturgical speech to God has been sufficiently apophatic in its adjectives (“infinite,” “eternal,” “immeasurable,” “incomprehensible,” etc.) to guard against the idolatry of ascribing sex or gender to the Godhead. To Mary Daly's aphorism “if God is male, the male is god” Wainwright says that the decisive retort is to deny the conditional clause. God is not male. (Wainwright, p. 118.) I am also not saying that excessively masculine and patriarchal language in liturgy is not a problem for contemporary listeners, nor am I saying we shouldn't make language regarding people inclusive where that was clearly the intent of the author. The New Revised Standard Version of the Bible has done well with this, in my opinion.

In the liturgies and proclamation of the congregation where I am Pastor we minimize the use of masculine pronouns referring to God and seek to find a wide variety of biblical images to speak about God. The battle about people language is over, I believe, and the church has reached a consensus that language about people must be brought up to conformity with the changes that have taken place in English. Accordingly, my congregation has amended its covenant to change “brotherhood,” “mankind” and other formally generic words that no longer are inclusive to their acceptable equivalents. This is a problem of English, as we recognize that no language ever stops changing. But the issue of the trinitarian name of God is not a translation problem, or a problem with the English language. That this issue of translation and language about people and the issue of “Father and Son” language in the Trinity are seen as identical has led to much of the current confusion.

The inclusive language issue is viewed by many as a simple issue of justice, and accordingly very frequently takes place without theological issues being raised at all. Let me cite a few personal anecdotes. When a colleague balked at the retaining of “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit” in the baptismal service of Book of Worship, and I suggested that it had been an ecumenical necessity which avoided otherwise dire consequences the reply was, “That is why I hate ecumenism. Why should we have to refrain from doing what we believe to be right because of other churches?” Another colleague suggested that we depersonalize all language about or referring to God along the lines suggested by some process theology. I said that I thought an impersonal God would do little justice to the biblical narrative and would lead inevitably to Unitarianism. The answer was “What is wrong with that?”

A certain “political correctness” around this issue has seeped into denominational enterprises. Certain official publications of the United Church of Christ have taken to putting “sic” after masculine personal pronouns referring to God within quotations from historic figures such as Reinhold Niebuhr, St. Augustine and John Calvin. Seminaries that abandoned doctrinal policies generations ago embrace “language policies” with no sense of irony. A nationally respected scholar was dismissed as a possible preacher for a denominational conclave when someone said, “We can't invite her. She doesn't use inclusive language!” (more specifically, she still speaks of “the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.”) It is difficult for me to imagine someone being barred in the same manner for having an inadequate trinitarian theology.

As a former seminary chaplain and chair of a Church and Ministry Committee I have witnessed repeatedly the conflict that results when seminarians trained by their professors to see these issues as paramount take their places in churches where their first order of business is to change the “sexist” Gloria Patri and Doxology. Congregations characteristically resist such attempts to tamper with the sacred things of their faith. Church history is replete with examples of the faithful people of God resisting changes in liturgy, especially of the parts of the liturgy that are theirs, that they either say or sing. Horace Allen has brought it to my attention that this is why we have little indigestible nuggets of older liturgies in the liturgies that replaced them; the people of God won't give them up. Thus we have a Greek “Kyrie” in a Latin Mass, Latin words, like Gloria Patri in Protestant English liturgies, and an Elizabethan "Lord's Prayer" in an otherwise modern language liturgy. In worse cases the seminarian or newly-minted ordinand sees only an intransigent congregation and they soon become her or his enemy, which is bad for congregations and ministers alike (although sometimes it does satisfy the well-developed appetite some ministers have for martyrdom.)

Given all this it should come as no surprise that we have spawned a reactionary organization. The Biblical Witness Fellowship, a conservative renewal movement within the United Church of Christ, has recently laid a charge of "apostasy" at the door of the national leadership for a long list of perceived failures in upholding the faith, among them the acceptance of the radical inclusive language agenda. That this is not good for the church goes without saying, but the vehemence of the charge and the defensiveness and lack of understanding from the leadership convinces me of a widening gap between the plausibility structures of denominational hierarchies and many people at the grass roots.

In my own congregation we have just looked at the issue of the Gloria Patri since our Minister of Music has written a new tune, and the question was raised whether we should use the opportunity to begin using the Gloria from Book of Worship. After much soul-searching on the issue we decided that since the church did not yet know its own mind on the subject we would retain the status quo, which does at least have nearly two millennia of Christian liturgical practice behind it.

The National Conference of Catholic Bishops in their Criteria for the Evaluation of the Inclusive Language Translations of Scriptural Texts Proposed for Liturgical Use (November 15, 1990) offers this guideline: “In fidelity to the inspired Word of God, the traditional biblical usage for naming the persons of the Trinity as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit is to be retained.” (p. 8) That seems right to me.

An address given to the Massachusetts Commission on Christian Unity on March 3, 1992 at Pope John the XXIII National Catholic Seminary at Weston, Massachusetts. This also appeared in Prism ,Volume 7, Number 2, Fall, 1992.

No comments:

Post a Comment